Ejaz Art Gallery’s latest display titled “Elsewhere” features work by six fresh graduates from NCA – Adnan Ali Umrani, Arghawan Hanif, Imran Gul, Maha Omer, Moin Rehman and Muhammad Reza Khan. I had the chance to interview them for their thesis display as well, so it was refreshing to see many of their new pieces on display. The exhibition is appropriately titled “Elsewhere,” as the compositions defy conventional logic, plunging into an otherwordly realm where realism and imagination entwine, creating a surrealistic aura. One thing that defines all of these pieces is an intense attention to detail– the fine brushstrokes that bring the unconscious to the front and allow you a peek into the artists’ minds and their visual dialogue. The works range from being an exploration of human existence to an intersection between spirituality and organized religion, a topographical view of our world and the merging of ways between childhood and adulthood.

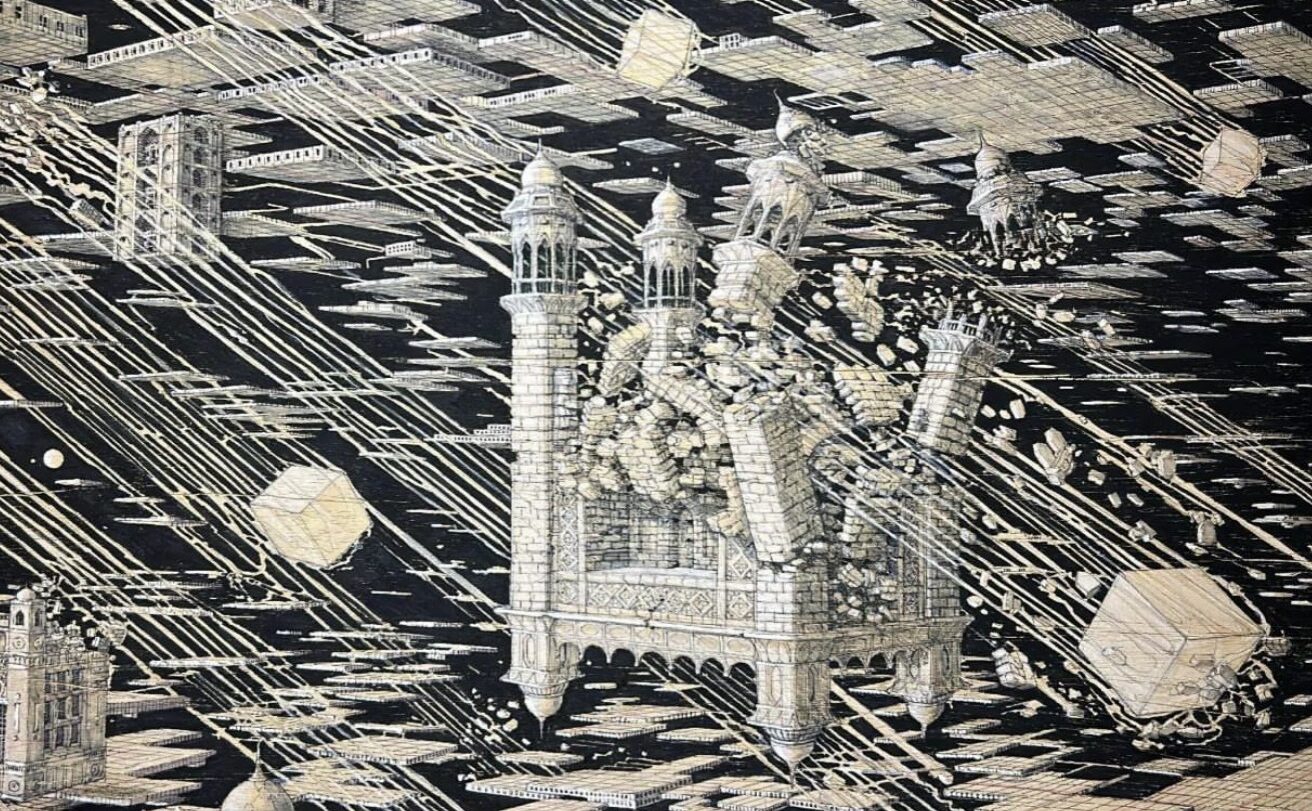

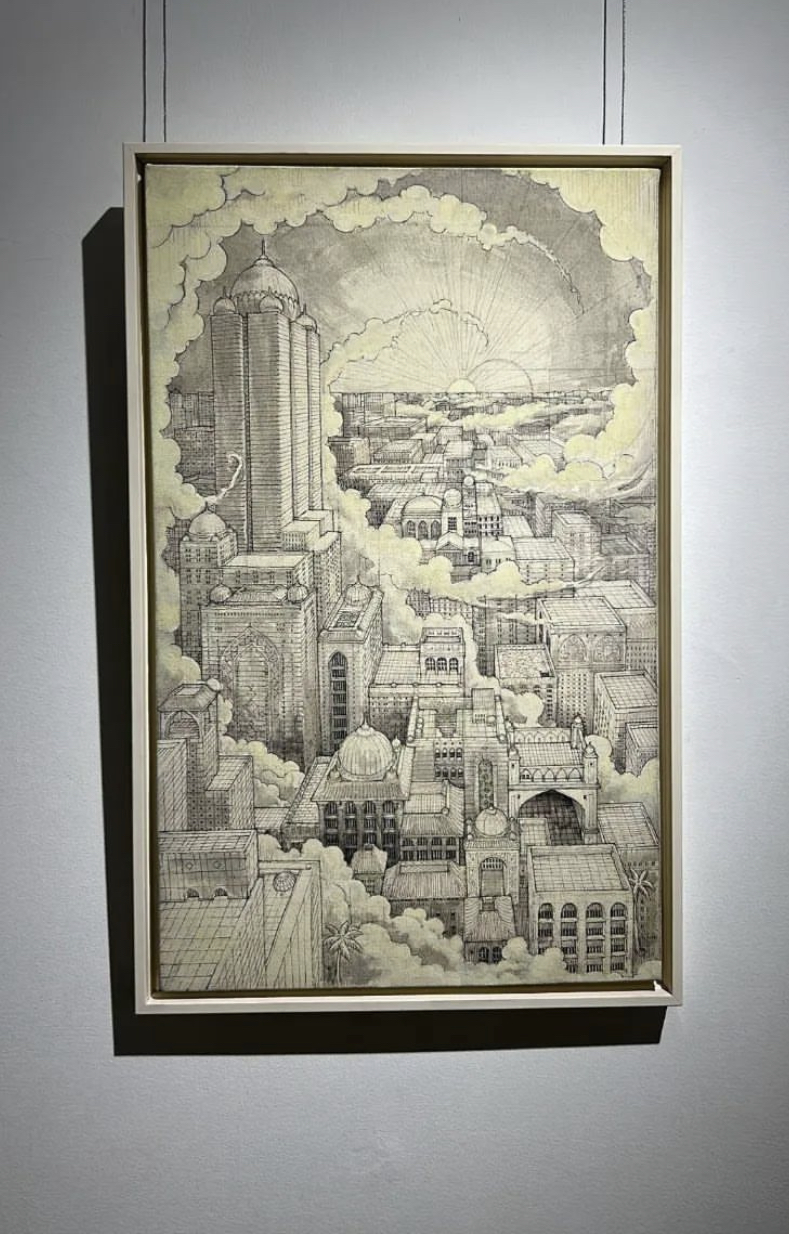

I first had the opportunity to talk to Moin Rehman about his work– a friend and I were taking in the intricacy of details represented in his work and contrasting it with the level of detail we had observed in his display as well. My friend in general was a huge fan of the geometric patterns and the level of delicate intricacy that defines his work since the thesis display– I remember being enamored with his vision of disintegrating cities and architectural structures from different cultures and faiths amalgamating in a range of colors– as if the work said, “There is beauty in destruction, and the idea of finding beauty in what destroys us and dismantles is the purpose. Everything is beautiful until we make it violent.”

We got the chance to talk to Moin Rehman, and he explained to us the use of geometry in his work. It is something that he believes is an innate part of our world; if you look at nature, you see recurring geometrical patterns in the flowers, in galaxies and in the human existence itself. To then explore it then means taking the bounds and facets of geometry and using them as something to validate his artistic vision. As for the recurring architectural landscapes in his work, he explains that his interest in architecture and history intersected to define his signature style.

The work at this display in specific can be examined as these strands intersecting and then converging, in titular red, blue and green, each color featuring architectural visions from different Abrahamic faiths. They are interconnected, yes, but they are also very different, and that is what defines their beauty. In a talk with Moin, he said: “Personally, I am an atheist yet still wanted to explore the major Abrahamic religions. I always keep saying that there are more similarities in religion than differences if you actually put in the effort to study them.” Thus, this particular artwork in the display was an ode to the similarities rather than the differences that we so often hyper-fixate on, which then manifest as violence. He pointed out the minute details to us: “There is a lot of symbolism if you look up close, Christianity is one of those religions which really revers saints and sculptures being made and you can see them depicted here if you look up close. I have included all sects from Islam as well– it is all in the details and the little symbolism that I made this stand out.” He also discussed how he had more freedom to explore what he wanted to since the prior display, and could take the reins of his own creative endeavors and he has been making full use of that to raise questions about social stigmas and become the voice of all social strata rather than just one.

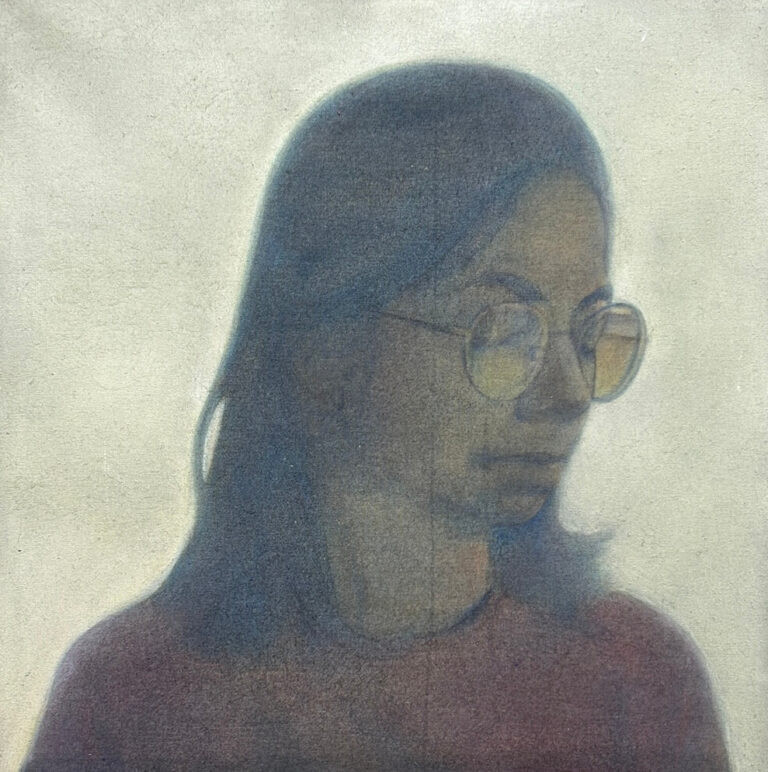

I also got the chance to be in conversation with Maha Omer– I found the use of textures and depth of dimensions in her work very striking. She uses surrealistic imagery and gives it an almost three-dimensional vision with the use of her preferred medium to give an artistic representation that encapsulates your senses on all levels. She described her artwork as being “interactive,” indulging in which makes it fun for her not only as an artist but evokes a sense of joy and ease in the viewer as well. It takes a lot of ideas from sculpturing, as she told me, and discusses: “…the duality of human nature, the inherent contradictions, and the constant choices we have to make. That constant paradox and the space between that paradox is what I want to discuss.” Again, delicacy and intricacy are something that stands out in her work– combine that with the use of dimensions, you have something that is going to give you a vision that is not one-dimensional but uses all your senses, especially the sense of sight. It is light and breezy on the eyes with the use of saturated tones and pastels contrasting each other and immersing the viewer in a realm where the boundaries of reality are expanded and the possibilities are endless. It was lovely conversing with her about her work and its purpose.

While I was not able to converse with Muhammad Reza Khan, his use of vibrant colors and topographical visions in his art was a salient feature. I was reminded of the topographical maps you often view in textbooks related to geographical weather conditions– cobalt and azures for bodies of water, hues of green for vegetation, and languid browns to represent the earth. You could see it reveled in the sights and complexities of nature we place aside and how they tie in together to give us a vision. Even during the thesis displays, I had taken note of how heavy the inclusion of botanical features was in his art. I, for one, have studied botany in my years through pre-medicine (albeit it being one of the less favored disciplines of Biology), and it was utterly beautiful to see nature in its glory– all ideals and manifestations of it. His description of his work put it better than I can: “Since childhood, I would step out of my home and wander away from our small town towards the mountains and the environment around me. The hike-up offered this sense of peace and became a safe pondering spot at an early age. Upon coming back to my home, due to the pandemic restrictions, there was nothing to do, which is why I decided to revisit these places, this paved a path of self-exploration and becoming more connected internally and spiritually after spending time in isolation.”

Arghawan Hatif’s artwork was defined by the intersection between childhood and adulthood– the use of striking colors and experimentation with the medium is what made it all the more special. It evoked a deep sense of nostalgia within me– the simplicity of a child’s attempt at capturing their vision of the world versus an adult’s and how they grow to find solace in perfection. This juxtaposition is what makes her work close to the heart– imperfection fusing with perfection to enrapture the audience. Arghawan describes her miniature paintings as “a subversive exploration of the uninhibited quality of children’s drawing. It revolves around the idea of Freedom, purity and simplicity. You may observe the striking use of color, processed through a spectrum of experimental techniques.”

Adnan Ali Umrani’s charcoal on paper shows you the suburban landscape shrouded in a lonely, desolate vision– the figures represented in the work are in spaces usually choke full of people yet still forsaken by modern-day loneliness. I have often talked about how despite being so interconnected, minutes away from your loved ones, you still feel as if you’re suspended in a reality that isolates you. The new-age loneliness is more visceral because it feels as if you are lonely in a room full of people and Adnan captures that in his work. The use of charcoal, with its expressive and versatile qualities, allows the artist to convey the organic textures, shadows, and depth of the natural elements. The absence of color becomes a deliberate choice, enhancing the viewer’s focus on the composition and the raw emotions evoked by the scenes. The interplay between light and dark conveys a sense of mystery and contemplation, inviting us to reflect upon our own place within the natural world. To conclude, these works transport us to a reality we prefer to ignore too often.

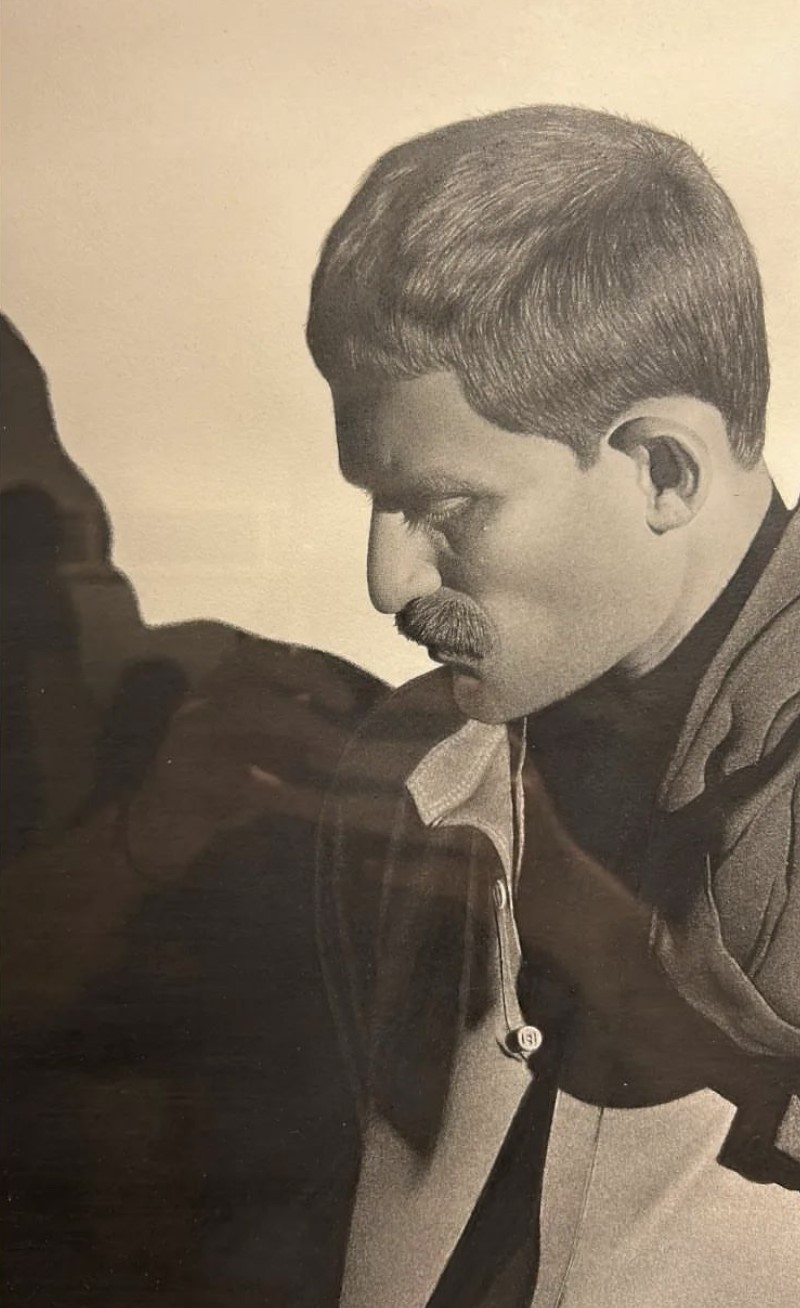

I was also able to talk to Imran Gul about his hyper-realistic art pieces– they are distinctive because they capture the very soul and every minute detail of the person they are representing; details which often go unnoticed. And these people represented and modelled are from the strata of society we choose to oversee because we do not want to indulge in their life, their choices and their personhood. We are divorced from the idea of them, living our lavish, cultured lives, while our paths intercede on the daily. In his previous conversation with me at his thesis display he had mentioned he decided to find his medium in the mundane and banal things of everyday life, and in this banality, he found the beauty of details. He talked about how we do not register details very often, but through his art, he was able to capture those little details and immortalize them in art. One thing I did notice was the indulgence in the subtility of emotion in these characters depicted– their forlorn gazes, smiles, and faces of shock or disdain all had the minute details we forget to view in even the individuals closest to us in life.

However, the main focus of my questions was something I had been hoping to put under the lens for a long time– hyper-consumerism and elitism in art circles which divorced the majority of the population from being consumers of art and restricts it to the petite bourgeoise who treat it as a commodity to be consumed, purchased and collected, rather than respecting the artist’s intent behind their work. I was reading up on gallery etiquette because I wanted to notice whether these behaviors were respected by these connoisseurs of art– the majority of people look at an average work of art for 17 seconds. We look for a fairly Instagram-able picture to show off our ‘cultured’ interests, rather than fixating on the whys and how of creative endeavors. It is a status symbol, often not with the best intentions. The starving, the ones stricken by poverty, do not have the opportunity or the time to indulge in art because they are too busy trying to survive the hapless and innate greed of the current-day neo-liberal hellscape. In an interview, Arundhati Roy stated: “Can the hungry go on a hunger strike? Non-violence is a piece of theatre. You need an audience. What can you do when you have no audience?”

I discussed this with some of the artists present. Moin stated that confronting capitalism in his artistic lens was too strong a word– he would rather say he discussed it through the subtle details in his work by including societal issues on a micro and macro scale– however, he did have qualms with the way people chose to consume his work. It would be a quick look, a few clicks on the camera, and they were done, rather than trying to find the deeper purpose behind it. And what is art if it does not evoke conversation, what can you do if the audience is not prepared to indulge in it?

Maha was of the same opinion– she stated that it was something she struggled with on a daily. “People come there because they think it’s a good place for an Instagram story, you know? Like, I can say it serves one purpose, but that is not the intention. The artwork is being commodified, and the artist’s intention should be respected in that regard. If you come into the gallery, there’s a certain decorum you need to respect, give respect, and give them time. You just look at them for what they are, not use your phone, just put them in your bag,” she explained in a conversation with me. She also elaborated on the categorization present in art circles–where some art is high art for the consumer and other is frowned upon as low art. The elites prefer a certain type of art and put it into a narrow, four-walled box to dissect. “It’s unfair, but they also rule the art world,” she went on to say. For her, it takes away the semblance of authenticity an artist hopes to achieve with their work and urges them to mass-produce art for sale. They have to fit the perception of what the masses want and ignore their creative freedom or nuance.

In a conversation with Imran at length, he mentioned how it felt as if art had been divorced from its purpose– as if it is almost not art anymore. “It doesn’t seem like people are engaging with your work anymore, it is more as if you’re a salesman presenting your goods to a prospective buyer, that’s how I felt at my thesis too.” To remove the meaning and purpose behind a work of art and reduce it to being an investment made him feel as if he was less of an observer there to express himself, and more of an observer present to sell out his work. This takes a toll. Also, you have to remember the prerequisites of choosing a reputable place to display your work at rather than just the craft itself– it is a very deliberate process. He talked about how surreal it felt to go back to Badin, his hometown, and interact with the models he painted. It was overwhelming at some level to observe these people up close and personal– they barely knew him, while he had spent hundreds of hours at length observing everything about them; from a singular crack in their nail to a birthmark. It felt as if he knew them more than they knew themselves and he became a middleman between them and the person willing to buy his work. However, he did state that he did not exactly mind the work environment despite the sudden change; it can be quite a fun challenge to imbue oneself in.

For me, I felt as if the hyper-commercialization of art perpetuates a cycle that prioritizes financial gain over artistic integrity and can hinder genuine dialogue and critical engagement. Elitism within art circles perpetuates a system that upholds privilege, exclusivity, and a narrow definition of artistic merit; you fall victim to institutional biases, established hierarchies, and exclusionary practices. It often creates barriers for underrepresented artists, stifling diverse perspectives and perpetuating a homogenous art canon. The ramifications of elitism extend beyond individual artists, shaping the art discourse and limiting the breadth of voices and narratives represented. However, artists who navigate the intersections of art, activism, and social critique offer a counterpoint to the dominant narratives, provoking critical discourse and promoting inclusivity. The only way we can cohesively combat this is by exploring grassroots initiatives, community-based projects, and digital platforms; it will allow us to uncover possibilities for democratizing art and fostering a more accessible and equitable creative landscape. Embracing collaboration, diverse representation, and socially engaged practices, artists and institutions can challenge the prevailing systems, promoting a more inclusive and socially conscious artistic ecosystem.

Pakistani art has always been a mirror of the nation’s vibrant culture, rich traditions, and

Owning artwork is a joy, but keeping it clean and preserved can be a challenge.

As an artist, your work is not just an expression of creativity — it’s also