Casim Mahmood represents the often forgotten/ ignored human beings in his sculptures and paintings.

Like many other articles of human need, shoes assume their owners’ identity. The way these are polished, cleaned, treated (heels rubbing away on a certain side/ angle), the person’s choice in style, colour, material, as well as his/ her purchasing power and social status. A pair of shoes also betrays its wearer’s mindset, aspirations, past and present: the life of misery or luxury. The same pair worn by a labourer becomes different from a doctor’s, because of its shape, condition and care.

After being used for some years, our shoes can become our self-portraits, an image that does not contain our likeness, but our habits, size, tastes. Vincent van Gogh painted a pair of old shoes (Shoes, 1888), which for many, including Martin Heidegger, belonged to a peasant. However, the American art critic Meyer Schapiro in his essay, The Still Life as a Personal Object – a Note on Heidegger and Van Gogh, seeks to demolish this assumption, claiming that these boots were the painter’s. Some critics still believe that the Dutch artist depicted the shoes of some impoverished person he empathised with.

Actually the life of Van Gogh – like many other landscape artists, was not different from an ordinary worker’s. A painter had to trudge on unhewn stones, in mud, on sand, under the blazing sun, sometimes in the water, roughened fields, uneven pathways to capture his subject. In that sense, a painter’s activity is far removed from somebody with a white-collar job, and closer to a farmer or labourer’s routine. Hence, the artist’s work outfit is not dissimilar to a motor mechanic, brick layer or pipe fitter’s.

This comparison and connection is even more accurate in the case of a sculptor. While creating art in their studio; carving, casting, moulding, welding, soldering, he/ she looks like a factory hand. Overalls, goggles, gloves and boots are the same as acquired by those doing menial work. Casim Mahmood, in his solo exhibition, Anonymous (May 24 to June 12, Ejaz Art Gallery) is drawing this parallel, between an artist and an ordinary worker, mainly through several pairs of shoes, made with metal pieces that resemble wearables but are actually worn-out, lack sheen and are shapeless and devoid of comfort. Seeing these scorched boots, I recalled passing a truck in Gulberg, which was put to fire during the recent mob violence in Lahore. The metallic skeleton of the charred vehicle was not too distant (both in terms of location and aesthetics) from Mahmood’s series of shoes displayed at the gallery, having the look of objects stripped of beauty, utility – and the rationale to exist.

In a sense, Casim Mahmood has excavated the essence of the shoes resulting from a labourer or an artist wearing those. He has forged these rugged shoes in metal with paint adding the feeling of rust, hence decay and disuse. These pairs – undoubtedly the best pieces at his solo – denote a familiar but extraordinary truth.

When a visitor goes to a gallery and confronts a painting or a sculpture consisting of a human body, he/ she admires it but cannot enter it, the other body. On the other hand, a pair of shoes invites a spectator to become a participant. One is tempted to put one’s feet in these objects on display – not unlike the products one is shown at a shoe store. The reality is that one cannot, because a painting or a sculpture of shoes, no matter how remarkably reproduced, belongs to art; and in case of Van Gogh’s canvas – to peasants, labourers, ordinary workers: those who exist on the periphery, but never become part of our usual existence (imagine the visit of a handyman, for which the household rhythm is disrupted).

When a visitor goes to a gallery and confronts a painting or a sculpture consisting of a human body, he/ she admires but cannot enter it. However, a pair of shoes invites a spectator to become a participant. One finds it tempting to put one’s feet in such objects on display – not unlike the products you are shown at a shoe store.

In a way, the worn-out shoes at the Ejaz Art Gallery, like Van Gogh’s Shoes, belong to the artist. Not that the sculptor could slide his feet in these impossible footwears, but their formation alludes to his position in the Pakistani art world. An accomplished artist, with a specific style, Casim Mahmood may have reconciled with his status as an outsider. He is not seen much and is definitely not part of usual group shows. Although he studied at the Hunerkada College of Performing and Visual Arts, Lahore (1997-2001), he calls himself a self-taught artist яндекс

Since he left his alma mater, he has never desired or attempted entering the closely guarded network of Pakistani art. However, he keeps on producing distinct artworks, even if he is not widely known. In his three-dimensional pieces and metal relief paintings, one comes across the other, a human being around us who remains anonymous. We refer to him as a chaiwallah, driver, chowkidar, office boy, peon, without ever bothering about his identity, or addressing him by his name. You see such individuals in the streets, in public transport, at work places, eager to gather his meagre earning. Casim Mahmood represents this unknown multitude in his sculptures and paintings: men made in metallic sheets standing alone or in groups, carrying suitcases or drinking from metallic cups.

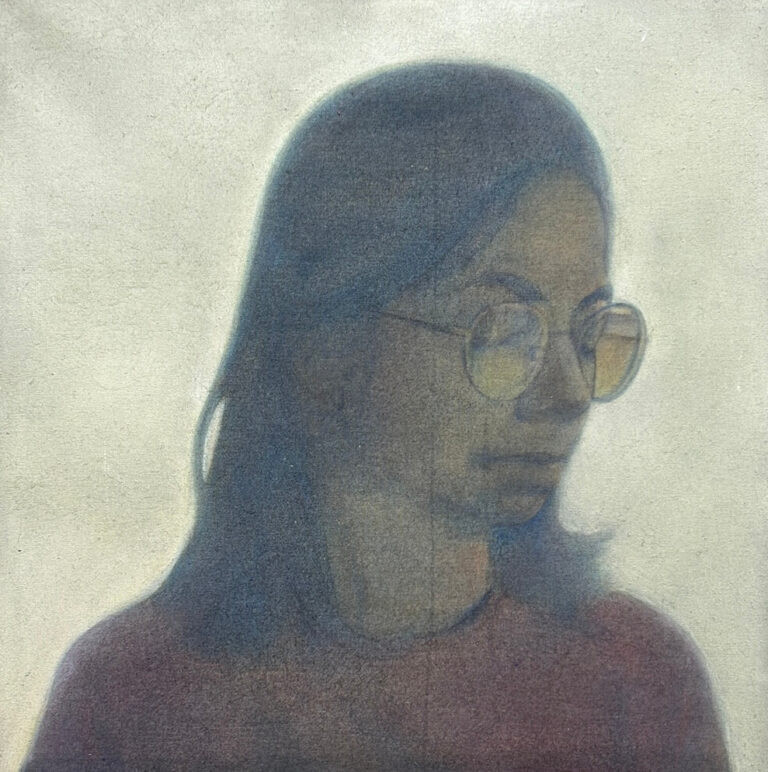

The fabrication and the material allude to some atrocity that has burned their outer skin and inner organs. Mahmood has similar characters in his paintings, where they are engaged in a number of activities. One such person is holding his tiffin carrier; another is cleaning his teeth; yet another licking an ice-cream bar; or opening the lid of a bottle with his mouth; clasping to a handbag; holding a teacup; sitting idly on a stool; or standing aimlessly. The acts are normal, mundane, unnoticeable: real. This body of work is far more honest than a group of men in staged scenarios such as a flower dangling from their lips or a bird perched on their shoulders.

One understands from his statement that Casim Mahmood aims to depict “ordinary, anonymous men, forsaken and left far behind, who quietly endure their forgotten existence”. Intriguingly, the artist refrains from representing exotic beings or those ethnically or sexually marginalised. His subjects seem to be regular guys you rub shoulders with in a bazaar, on a street, at a mosque. Their faces are cartographies of their miseries. Mahmood assembles his sculptures as darkened portraits of hardened individuals, with a superb skill in delineating their movement and action, while revealing marks of welding, residue of soldering that could also be read as moles, spots, warts in these desolate figures.

Through these dark, skeletal, suffering characters, Casim Mahmood seems to be presentinga subjugated population. Maryse Conde in her novel,The Gospel According to the New World, observes,“skin colour is a signifier. If it is dark, it means the family is living in poverty.” In their formation, appearance and colour, these men look like social outcasts as well as the Afro-Americans. Knuckles, hands, arms, eyes, feet, and bodies of these individuals repeatedly remind of one of the black population. Though the visual artist is based in Lahore, he also has a band (East Side Story) and his music connection is a factor for representing – and appreciating the dark and downtrodden people in pain. Casim Mahmood has been playing Jazz or Blues for 25 years; and according to David Scott Kastan with Stephan Farthing (On Colour), “Invented by African American, the ex-slaves and sons and daughters of former slaves, the blues mixed work chants, folk songs and spirituals to produce a music of loss and of longing.”

Pakistani art has always been a mirror of the nation’s vibrant culture, rich traditions, and

Owning artwork is a joy, but keeping it clean and preserved can be a challenge.

As an artist, your work is not just an expression of creativity — it’s also